Everyday Art

See how artists make the ordinary extraordinary.

Idea One: A Family Portrait

The painter Berthe Morisot lived in Paris, France, during the 19th century. At that time, being a serious artist was an unusual occupation for a woman. But Morisot was determined to follow her interest in art and develop her talent into a career.

As a woman, Morisot stretched the rules of society in becoming an artist. Her paintings, however, show women living a traditional life in the private world of home and family. Morisot’s own family members and close friends served as models, posing for her in familiar settings. In 1879, a daughter was born to the artist and her husband, Eugène Manet. Throughout her childhood this little girl, Julie Manet, was often the subject of her mother’s artwork. She was the couple’s only child.

In The Artist’s Daughter, Julie, with Her Nanny, Morisot’s quick brushstrokes captured a simple moment of home life. Julie is watching her nanny, Pasie, doing needlework. Both of them are absorbed in the activity of sewing. Their closeness to each other and to us (they are right up front in the picture) shows that they have a close personal relationship. Through the window, you can see Julie’s father in the garden of their Paris home. Perhaps he, too, is busy with some household task. Like a snapshot in a family album, this painting gives a glimpse of the artist’s family life.

French, 1841-95

The Artist’s Daughter, Julie, with Her Nanny, 1884

Oil on canvas

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Berthe Morisot and Julie Manet, 1880-90,

drypoint,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

bequest of Harriet C. Weed

Julie is fascinated by her nanny’s task.

Morisot portrayed herself at work with her daughter by her side.

Morisot’s daughter, Julie, was a regular subject of her mother’s artwork.

Portrait of Julie Manet, 1888-90,

drypoint,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

bequest of Harriet C. Weed

Morisot’s daughter, Julie, was a regular subject of her mother’s artwork.

Idea Two: Mixing It Up

When do you get to enjoy a chocolate treat? At parties or on special occasions? For dessert after a meal? In ancient Mesoamerica, people had chocolate at every meal, every day. The Maya, who lived in the region that is now southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, were one of the first cultures to discover how to make chocolate from the seeds of the cacao tree.

The Maya did not make the sweet, solid chocolate bars popular today. They mixed up a spicy chocolate drink. A combination of ground cacao seeds, water, and other ingredients like cornmeal, chili peppers, and honey, was poured back and forth between a pot and a cup until the concoction became thick and foamy.

All Mayan people, whether rich or poor, common or royal, drank this chocolate beverage as part of daily life. In addition, chocolate was often drunk during ritual ceremonies. Even Mayan gods were believed to like the liquid chocolate.

Special containers were made for mixing and storing chocolate. A simply decorated pot like this one would have belonged to a common Mayan household. Two grooves along the top edge reveal that it once had a twist-on lid. The four carved symbols are glyphs, the Mayan form of writing. Perhaps one of them tells how the pot was used.

Chocolate pot, 750

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Harold and Rada Fredrikson

These are drawings of the four Mayan glyphs on the MIA’s chocolate pot.

ceramic and pigment,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The David Draper Dayton Fund

The elaborate decoration on this Mayan vase includes a monkey holding a chocolate pot.

Idea Three: Concealing and Revealing

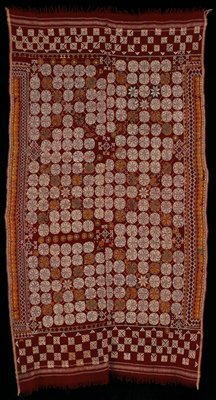

Women around the world throughout history have worn veils and head coverings for various reasons. In some cultures, veils are worn only for certain occasions, whereas in others, head coverings make up part of a woman’s everyday clothing.

In India, traditional everyday attire for women includes colorful fabric veils. Although worn for modesty and privacy, these head coverings may reveal information about the wearer. A veil’s color, pattern, material, and workmanship might show what region of the country the woman is from, which village she lives in, her social status, and whether she is married. Head coverings may also include symbols for the season of the year or an important social occasion.

For a special occasion, a woman would choose the right veil from her wardrobe. This head covering from India’s Rajasthan region is for the mother of a newborn son. Its yellow color announces the birth of a boy. Ten small lotus-blossom decorations stand for the nine months of pregnancy and the child’s birth month. A single large lotus in the center of the veil symbolizes the creation of a new life.

Unknown artist, India

20th century

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

Woman’s wedding veil (odhani),

late 19th-early 20th century.

Wool, cotton; embroidery.

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

Idea Four: Designed for Living

This kitchen’s compact work space was designed back in the 1920s by a young woman, the Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. She wanted to modernize, simplify, and streamline everyday household tasks. Built-in, labeled aluminum bins with convenient handles and pouring spouts held dry provisions. A swiveling stool near the sink and window made it possible to prepare food under natural light. Continuous countertops and a built-in garbage drawer encouraged cleanliness. Other modern features include an adjustable ceiling light, a pass-through to the dining room, and a drop-down ironing board.

The museum’s Frankfurt Kitchen is one of more than ten thousand that were built for the Höhenblick apartment complex in Frankfurt, Germany. With two million soldiers returning home after World War I, German cities needed efficient, low-cost housing. The modern design of the Frankfurt Kitchen spread to housing developments in other German cities.

At that time, most German apartments had two rooms, a kitchen and a living room. The heart and soul of a home was the kitchen, where cooking, eating, bathing, and even sleeping took place, while the living-room was used only on special occasions. The small, modern Frankfurt Kitchen freed up space for family life and relaxation in the rest of the home.

Austrian, 1897-2000

Frankfurt Kitchen, 1926-1930

Kitchen cabinetry and stove

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Funds from the Regis Foundation

Twelve aluminum bins in the Frankfurt Kitchen stored dry foods.

This container, labeled Feiner Zucker, was for sugar.

The continuous counter and pullout garbage drawer made short work of cleanup.

Idea Five: Common Goods

How long do you suppose people have been using glass? Over four thousand years ago, the amazing art of glass making got its start in Mesopotamia and Egypt. From there, it spread westward. The ancient Romans loved glass for its beauty and usefulness. As glass became more and more popular, the Romans discovered ways to make more of it, such as glass blowing.

Glass blowing began in Syria early in the 1st century. A person blowing air through a tube could form molten (hot liquid) glass into a bubble and then into all sorts of different shapes and sizes. Blown glass objects were quick to make and inexpensive to buy. Soon, people of all social classes could afford glass items. By the 1st century, glassware was found in households throughout the Roman Empire.

Although fragile, glass had many uses in daily life. Meals were prepared in and eaten from glassware; spices, oils, perfumes, cosmetics, and medicines were stored in glass vessels; merchants and traders packed goods in glass containers for transport and sale. Unlike the pottery the Romans had used before, glass did not keep the smell or taste of its contents, but it preserved flavor. And you could easily see whatever was inside a glass jar or bottle.

1st-5th century A.D., glass,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

gift of Mr. and Mrs. I. D. Fink

This intricate bottle was for perfume.

2nd-3rd century,

blown glass,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The Classical Art Fund

Related Activities

Family Album

Create your own family portrait. Use pencil, chalk, paint, or even a camera to make a picture of a family member at home. What jobs, chores, hobbies, or pastimes do they perform daily? Try to capture them in an everyday activity.

A Tasty Treat

Learn more about the history of chocolate and the Mayans role in its use. Check out the Field Museum online exhibition Chocolate to discover this ancient treat’s past.

A Colorful Life

Research the symbolism of colors in cultures around the world. Are particular colors worn on special occasions such as holidays or life celebrations such as marriage? Why is color important to people? What colors do people in your family wear on special occasions? What do those colors mean to you?

View FSA Photographs

Think about objects in your home that you and your family use every day. What items help you perform specific daily activities? Do you have things that an older family member once used every day but that you now consider special and precious? Which items that you use today will be special and curious to people in the future?