Henri Matisse

Drawings, paintings, sculptures, prints, and collages – Henri Matisse was a master artist like no other.

Idea One: It’s all about Drawing

Woman with Folded Hands, 1918-1919,

pen and india ink on white paper,

©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse did not plan on being an artist. He began his artistic career while working as a lawyer, by taking an early-morning drawing class. It was not long, however, before he went against his father’s wishes and became a professional artist. Perhaps because of those early classes, drawing always remained important to him.

Matisse’s drawings reflect the different styles and techniques he used over the course of his career. Works like Woman with Folded Hands are quick sketches that capture a moment, a form, or a feeling. Other drawings, such as The Music Lesson, where Matisse was experimenting with pattern, are carefully detailed. Matisse chose to simplify the figures in his drawings. But he could also do very realistic work, as in his lithograph Odalisque with Bowl of Fruit.

lithograph, ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Here Matisse is experimenting with patterns. Are the women the subject of this drawing or just a part of the pattern?

This image shows that Matisse was truly a master draftsman.

Idea Two: Master Painter

oil on canvas ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The three bathers in this painting are defined by dark outlines that separate them from the beach.

Matisse was influenced by the flattened figures in medieval and early Renaissance paintings.

Matisse was twenty years old and recovering from appendicitis when his mother gave him his first set of paints. She thought it might help fill his time. He started by painting humble still lifes and was soon studying the great masters.

Matisse was always independent. He began his artistic training in a traditional way but then left school because the professors taught only traditional, academic art. Yet he was open to learning from the past. In works like Three Bathers you can see the influence of medieval and early Renaissance artists in the darkly outlined, flattened figures.

Matisse belonged to of a group of artists called the Fauves (French for wild beasts). The Fauves used bright, random colors and vigorous brushstrokes to express emotions and experiences. Boy with a Butterfly Net, a nearly life-size portrait of a boy named Allan Stein, is one of Matisse’s Fauvist works. The landscape behind the boy is made up of broad bands of color too vivid to look natural: a deep blue sky, grassy hills of emerald green, and a sloping, brick-red path.

Idea Three: Sculpting Forms

bronze ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Just as he exaggerated the curves of Madeleine I, Matisse gave this figure a very long body and placed it at an exaggerated angle.

Matisse’s sculptures tend to be overshadowed by his paintings. Matisse turned to sculpture off and on, usually when he was having difficulty with a painting. It offered both an escape from his painting problem and a way to understand his subject better. In all, he created more than seventy sculptures.

Most of Matisse’s sculptures are small, freestanding figures. He made them first in clay and then had them cast in bronze. Madeleine I was his first important bronze sculpture. Matisse took great pleasure in manipulating the clay’s shape and surface texture. Often he made multiple versions of the same piece, either starting over or reworking an existing sculpture. Through sculpture he could study a three-dimensional form by moving all around it, before flattening it into a two-dimensional image in his painting.

bronze ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Just as he exaggerated the curves of Madeleine I, Matisse gave this figure a very long body and placed it at an exaggerated angle.

Idea Four: Balance in Prints

Three Apples and Plate, 1914-1915,

monotype print ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This page shows the kind of book illustrations Matisse created.

Besides paintings and sculptures, Matisse also produced more than eight hundred prints. Like sculpture, printmaking provided relaxation or distraction for him during especially challenging periods of painting. His prints often reflect the themes of paintings he was working on at the time. Nearly all are black-and-white, but they were printed by a variety of methods.

Matisse particularly liked to make transfer lithographs. Instead of drawing directly on the lithographic stone, he drew the image on a sheet of paper and then transferred it to the stone for printing. A lithographic print is the reverse of the image on the stone. One advantage of transfer lithography is that the printed image looks the same as the original drawing. Matisse also created monotypes. These are one-of-a-kind single prints made by coating a copper printing plate with ink, drawing on the inked plate, and then carefully printing the image onto a sheet of paper.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Matisse made many prints as book illustrations. However, he did not simply translate the author’s words into pictures; he tried instead to depict his own feelings about the text. Matisse also oversaw the design and layout of the books he illustrated. His attention to the details of a printed book can be seen in Poésies, by Stéphane Mallarmé. In all, Matisse illustrated eleven books.

letterpress ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Besides lithographs and monotypes, Matisse also made linoleum cuts, in which the image is carved into a block of linoleum.

linoleum cut ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This image was printed by transfer lithography. Instead of drawing on the lithographic stone, Matisse drew on paper and transferred the image to the stone, where it appeared in reverse. Printing reversed the image again, so the print looked just like the original drawing.

lithograph ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Idea Five: Creative Cutouts

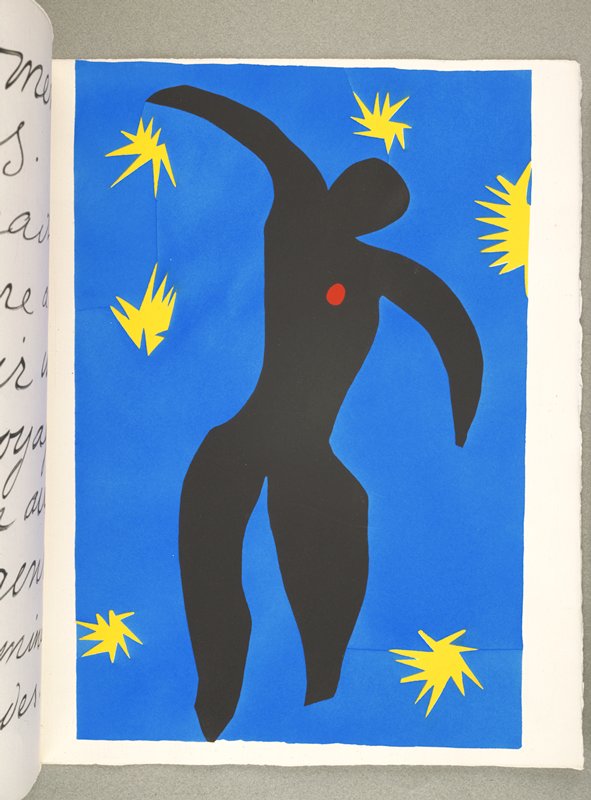

Jazz , frontpiece from Verve , 1945,

lithography reproduction of gouache cutout ©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Closely resembling Fall of Icarus, this is an example of how Matisse reworked the same theme many times.

Late in his career Matisse began experimenting with paper cutouts, which he made into collages. To make the collages, he first had his assistants paint white paper to give it a bright color. Then he cut out shapes, arranged them, pinned them into place, and finally glued them down on a sheet of paper.

Cutting the shapes himself gave Matisse complete control over the artwork. He called it drawing with scissors. Cutting into the paper left a clean edge, much like the clean lines of his drawings, but the weight of the paper against the scissors reminded him of sculpture. His work in this art form peaked with his book Jazz, in which colors and shapes convey the essence of jazz music.

Matisse’s cutouts look different from his other works, but they follow the same themes and continue his use of bright colors and pattern.

from the illustrated book Jazz, 1947,

printed reproduction of gouache cutout©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Closely resembling Fall of Icarus, this is an example of how Matisse reworked the same theme many times.

Les Codomas (The Codomas),

from the illustrated book Jazz, 1947,

printed reproduction of gouache cutout,

©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The freeform shapes of this cutout recall the flowing brushstrokes in many of Matisse’s paintings.

from the illustrated book Jazz, 1947,

printed reproduction of gouache cutout,

©Succession H. Matisse,

Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Colors and shapes combine to form a lively composition in this image from Jazz.

Related Activities

Look through Matisse’s Eyes

With a poster-size image or a still life as your model, re-create what you see, using only construction paper, scissors, and glue. Try to simplify the forms into blocks of color. Now you are looking at the world like Matisse!

Illustrate a Story

Matisse illustrated other writers’ works as well as his own. On a piece of unlined paper, write a short story and then pass it to the person sitting next to you. Now read the story given to you. How does it make you feel? What else does it make you think of? Guided by your own thoughts and feelings, illustrate the page. Then show the author what his or her work inspired you to create.

Create Cutouts

Following Matisse’s technique, use paint to color a sheet of white paper. Then cut out abstract shapes, arrange them on another sheet of paper, and glue them down. Matisse’s cutouts are considered artwork, so you should sign your masterpiece.

Practice Drawing

With a partner, take turns being model and artist. Practice the contour-drawing technique Matisse used in Woman with Folded Hands. Don’t have a partner? Try this the technique with a still life.