We hurtled down the steep mountain, leaving behind thousand-year-old temples and the pungent sulfur springs of the verdant Dieng Plateau. It was a long drive, and when we reached the city of Yogyakarta (Jogja) it was already late afternoon. Just in time for rush hour—urban Indonesia at its frenetic finest.

This marked a new stage in the 17-day exploration of Asia’s art scene undertaken by myself and Liz Armstrong, the MIA’s curator of contemporary art: our first opportunity to visit local art foundations and artists’ studios. But first we had to adjust. After the cool, misty climate of Dieng, the humidity and blazing sun of Jogja were paradoxically both a comfort and a cause for sluggishness. We motivated the next morning to meet our guide, Rismilliana Wijayanti, in our hotel lobby. Warm and quick-witted, she is currently the manager of Jogja Contemporary and had spent years working for important Indonesian art galleries. Several artists we met over the next three days called her “mama.” (We called her Ries).

Art on the Verge

Jogja’s art foundations are impressive, dynamic spaces, echoing the work they support. Many were founded by artists whose stock has soared during the Asian art boom of the past decade.

Now they want to give back to the artistic community from which they emerged, showcasing their contemporaries and offering entree into the global art market.

Cemeti Art House was the first art foundation of its kind when artists Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma established it in 1988. Liz and I dove into its current exhibition, taking turns lifting weights shaped like Buddha heads made by Jae Hoon Lee, attempting to experience serenity during each calorie-burning lift—perhaps a sly commentary on the commercialization and reinvention of “eastern” exercises such as yoga?

Other highlights were the Indonesian Visual Art Archive (IVAA), with the impressive Farah Wardani at its helm, which keeps an online and physical archive of pre-independence Indonesian art practices beneath its soaring wooden ceilings, and SaRang, where Jumaldi Alfi, the center’s gregarious founding artist, gave us a tour of the immaculately designed building. On display was a monumental, movable, disco-ball-like sculpture by Sara Nuytemans, a Dutch-born artist based in Jogja.

In front of MES 56 with founding members and artist in residence. From left to right: Risha Lee, Jim Allen Abel aka Jimbo, Syaura Qotrunadha, Woto Wibowo aka Wok the Rock, and Liz Armstrong.

At MES 56, a photography-oriented collective that disseminates and sponsors cutting-edge art projects, three of its incredibly hip founding members (who dub themselves the MES Boyz) introduced us to three equally hip female artists in residence, currently completing art school in Jakarta and Jogja. Guess who suddenly didn’t feel so hip.

Artists in Action

Visiting artists’ studios was just as inspiring. We met with soft-spoken Handiwirman Saputra, and I immediately gravitated towards an ingenious series, in which he crafts abstract sculptures out of non-biodegradable refuse, then elevates them to beautiful forms in magisterial oil paintings.

From these, I sensed both a rallying cry to preserve the country’s ecological equilibrium as well as a commitment to discovering pure artistic form.

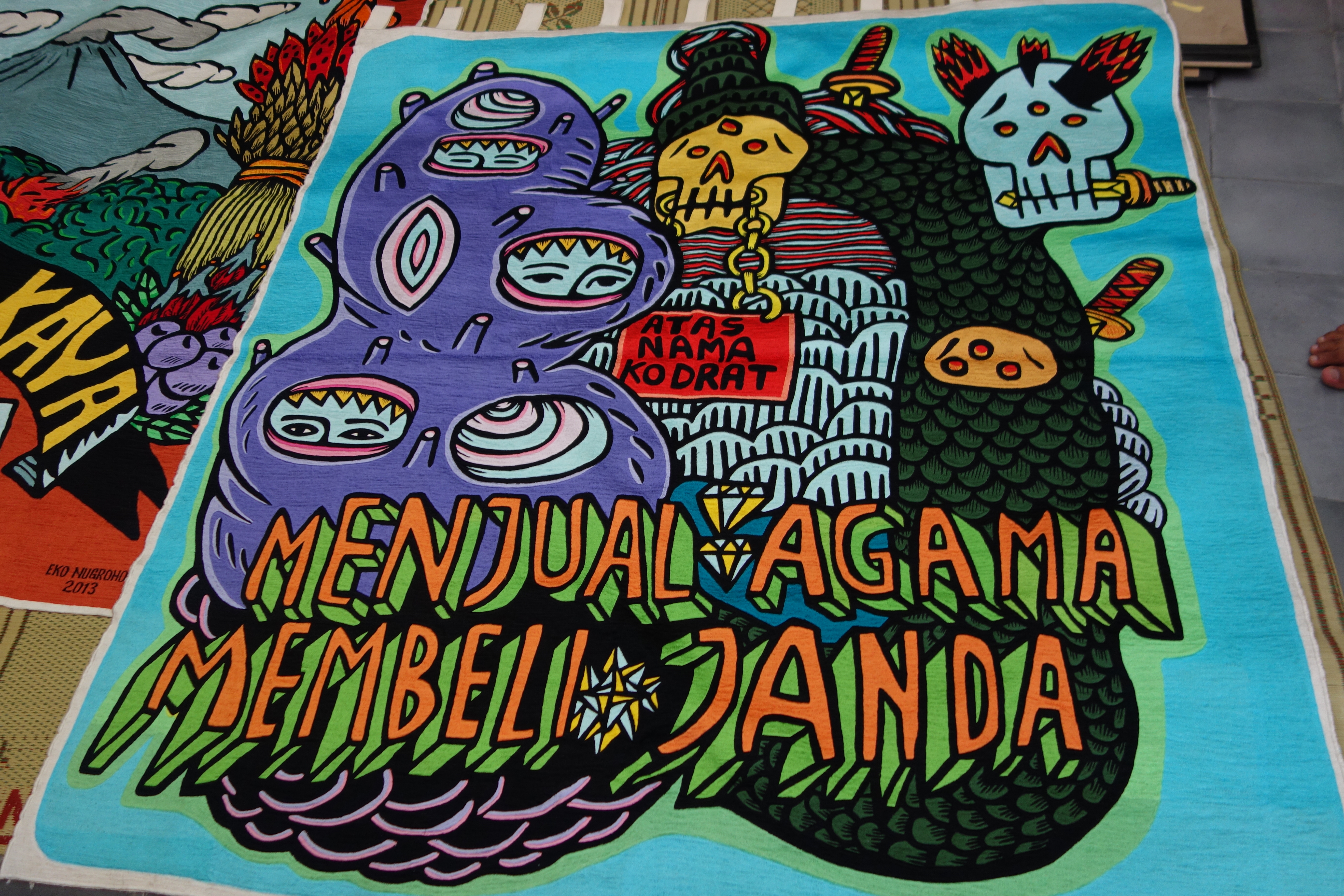

Eko Nugroho showed us his deceptively buoyant embroideries. Inspired by manga (Japanese comics), the work bears wry inscriptions such as “the universe widens and man narrows,” or “tolerance under a rock.”

Yet they have a strong satirical bite, hinting at the threat of totalitarian governmental control. Woven by local weavers, the embroideries also allude to the long tradition of textile making within Indonesia.

We enjoyed the company and hospitality of Entang Wiharso and Christine Cocca, a delightful artistic duo extraordinaire. Wiharso’s monumental graphite and aluminum sculptures adorned several buildings we visited, including the facade of the OHD museum, which houses the 2000+ object collection of the indefatigable Dr. Oei Hong Djien. Teeming with twisting bodies, that remind me of frescoes depicting hell in quattrocento Italy.

Titarubi’s work was the most immediately engaged in investigating history. She collects hundreds of nutmegs—a symbol of Indonesia’s once-central role in the spice trade—paints them gold, then constructs European monastic-like cloaks from them. They are transformed into shining signifiers of the Dutch East India Company’s past control over the country as colonial rulers, and reminders of the violence inflicted by the oppressive regime.

Leaving Indonesia behind, Liz and I headed to Singapore and spent a few days exploring museums and private collections. While we were there, we stayed at the fabulous Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI), an MIA partner (currently exhibiting the MIA-curated show, Edo Pop) that offers residencies to artists from around the globe.

By the end of our trip, our sandals were filled with sand, our bags overflowed with innumerable posters and books, and our minds brimmed with possibilities of future projects and partnerships. In our nearly three-week absence, Minnesota had flipped from a chilly spring into summer. But today’s forecast is this: more Southeast Asian art at the MIA! Stay tuned.