By Nicole Soukup

“It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.”—Audre Lorde

A popular meme asks: Can you name five women artists? How many artists on your list are women of color? How many identify as queer? Trans or gender fluid? How many are disabled?

Here’s another question: Why does any of this matter?

After all, we are facing a pandemic, economic fallout, and political turmoil. Roughly three billion people—nearly half the world’s population—are sheltering at home. And yet, is it not in times like these that we turn to art? Art can serve as a balm for our frantic, anxious lives. Art gives voice when words fail. It is now, in moments of crisis, that Mia’s core values of representation, inclusion, equity, and accessibility matter more than ever.

March is Women’s History Month. And this year also marks the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in the United States. But 2020 marks a lesser-known anniversary, as well: Twenty-five years ago, artist Elizabeth Murray attempted to curate an exhibition of women artists for the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). She couldn’t even fill a gallery.

This should not come as a shock. Historically, museums and art institutions have consciously and unconsciously promoted the work of European and American male artists, over all others. In 1971, in her groundbreaking essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, American art historian Linda Nochlin outlined the systemic issues supporting the suppression of women artists, including the opportunities available almost exclusively to white men for centuries, like studying nude figures or attending certain art schools. In the 1980s, artists and activists like the Guerrilla Girls began calling out the inequities of art institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of Art. (They called out Mia in 2016.)

Over the past two decades, MoMA and other institutions across the country have been diversifying their collections. While authors like Anne Anlin Cheng, Roxane Gay, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and adrienne maree brown have helped shift how we think about feminism, countless academics, artists, curators, collectors, and activists have been calling for change in the art world. Landmark exhibitions have promoted artists who were overlooked for decades, including “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution” (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; March 4–July 16, 2007), “Radical Women: Latin American Art 1960 to 1985” (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; September 15–December 31, 2017), “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women,” 1965–85 (Brooklyn Museum, New York; April through September 2017), and “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists” (Mia; June 2-August 18, 2019).

Women have long been a part of Mia’s collection, however, they have often been overlooked or marginalized. For example, do you know of Hollis Sigler’s painting You Remember How Very Special the Moment Was, from 1981? Sigler, a Chicago-based artist, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1985. Shortly after her diagnosis, she began the Breast Cancer Journal, a collection of 100 objects encompassing paintings, drawings, watercolors, prints, and cut-paper pieces—including the work in Mia’s collection. At a time when many queer artists were navigating the AIDS crisis, Sigler, a lesbian, used art to navigate her own journey through terminal illness. By 1992, shortly after You Remember How Very Special the Moment Was was acquired by Mia, Sigler was informed that the cancer had spread to her bones. She passed away at the age of 52 in 2001.

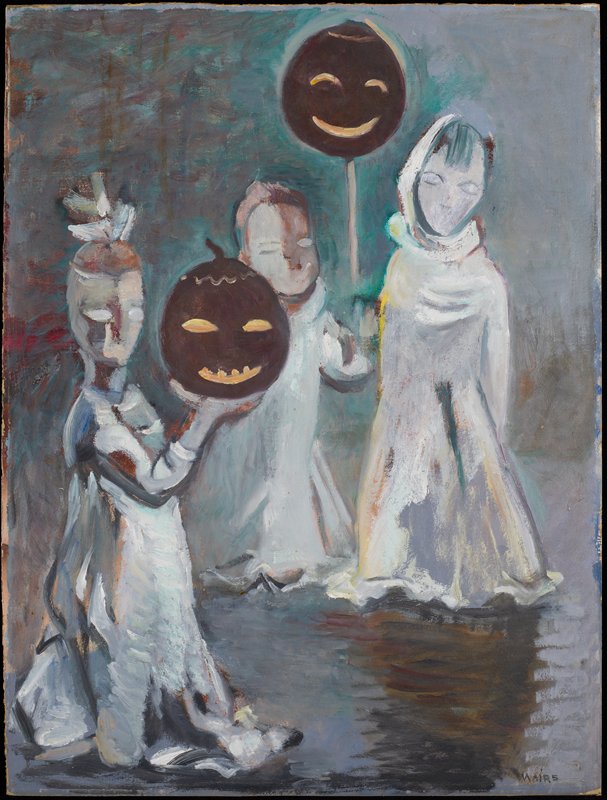

Clara Gardner Mairs’ work Halloween, made around 1920, came into the collection in 1945. The artist was born in Hastings, Minnesota, in 1878. After attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, she returned to St. Paul, where she met her lifelong partner, artist Clement Haupers (22 years her junior). Much of her work depicts daily life in the Twin Cities during the early and mid-20h century. As a young mom, I am empathetic to the sheet-wrapped children holding pumpkins in the air. Mairs captures the quirky spookiness that Halloween inspires. The reflections on the ground recall the icy trick or treating of my own Minnesotan youth: puffy coats, thick boots, and mittens topped off with a simple witch hat.

In her book Emergent Strategies: Shaping Change, Changing World, adrienne maree brown stated, “I think it is healing behavior to look at something so broken and see the possibility and wholeness in it.” At Mia, we strive to acknowledge the flaws in our institution. In recognizing that there are gaps in our historic collection, we acknowledge the possibility to bring marginalized artists into the fold. For the past fifteen years, Mia’s curatorial team has been actively reshaping how we think about the histories of art. Below are five works by women artists that have recently come into the collection.

1) In The Soaring Hour (Self-Portrait), from 2018, Delita Martin addresses her own dual existence between the physical and the spiritual. The work has been on view at Mia as part of the exhibition “Mapping Black Identities.”

2) Martha Rosler’s Minneapolis, from 1991, is one of five prints in her “In the Place of the Public: Airport Series.” The series, started in 1983, feels even more poignant now as we consider how interconnected we really all are. All five works were on view at Mia when we closed.

3) Aliza Nisenbaum’s painting Nimo, Sumiya, and Bisharo harvesting flowers and vegetables at Hope Community Garden, from 2017, is part of the touring exhibition “When Home Won’t Let You Stay,” which was on view at Mia when we closed to #StayatHome. It’s a beautiful portrait, commissioned by Mia to celebrate and elevate the communities that surround the museum. In this instance, Nisenbaum depicts Nimo, Sumiya, and Bishara sitting in the garden where they spend their time.

4) Mika Rottenberg’s Cosmic Generator (Lettuce Variant), from 2017, examines immigration, trade, and the audacity of bureaucracy in our hyper-globalized world. The work is scheduled to be on view later this year.

5) Pao Houa Her’s Untitled (Portrait) and Untitled (Como Park Conservatory) from her series “After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw,” 2017, are powerful testaments to the ability of photography to tell a story. Both the portrait and the landscape relate the Ponzi scheme that conned elder Hmong Americans into giving up their life savings for a piece of a new Hmong homeland, a dream for many who immigrated to the United States following the Vietnam War. The work challenges expectations of what home means and highlights generational differences.

Top image: Aliza Nisenbaum’s Nimo, Sumiya, and Bisharo harvesting flowers and vegetables at Hope Community Garden, from 2017.