The story of the Purcell-Cutts House windows is kind of a race to the finish line. The house was supposed to be completed in time for architect William Gray Purcell and his family to move in by Christmas 1913. The exterior construction was just wrapping up in the fall, and the house had to be sealed up before Minnesota’s winter hit, so the workers could finish the interiors.

The windows weren’t ready, but the local art glass contractor, E. L. Sharretts’s Mosaic Art Shops, had an idea: They would bring over every piece of sheet glass they had available to tack into the frame stops, a temporary fix while they finished the art glass windows. It made for a very interesting patchwork look to the house, and Purcell recalled the effect in his Parabiographies written in the 1950s:

“Arriving at the job next evening, I was struck dumb at the sight, and for the mental condition of the neighbors there were no words. In all the 72 window openings were great sheets of bright blue, yellow, green, red, wine, orange glass. There were sheets of frosted and office partition glass, diaper church panes with angels, mottoes, and shields. It was a sight for an asylum of trolls. The neighbors had thought the house at best was wholly insane—not one thing inside or out was like any house they had ever seen—and this was the final neighborhood insult.” (No photos mark this for the record, but one panel of opaque glass is still hidden in the upstairs master bedroom closet.)

What the house was destined to have—and did have by the time the Purcells moved in—were sparkling, semi-transparent screen-like windows with a diamond pattern and rectangular borders, designed by George Grant Elmslie, Purcell’s architectural partner.

Eight of these dynamic, nearly 103-year-old windows are being conserved this summer, and it’s so cool when the historic record jibes with the material evidence. Those at the (MACC) who are working on the windows now as part of the have noticed some interesting bits about the windows that are consistent with the story of Mosaic Art Shops racing to finish the windows.

Eight of these dynamic, nearly 103-year-old windows were conserved this summer, and it’s so cool when the historic record jibes with the material evidence. The experts at the Midwest Art Conservation Center (MACC) who have worked on the Purcell-Cutts House window conservation project have noticed some interesting bits about the windows that are consistent with the story of Mosaic Art Shops racing to finish the windows.

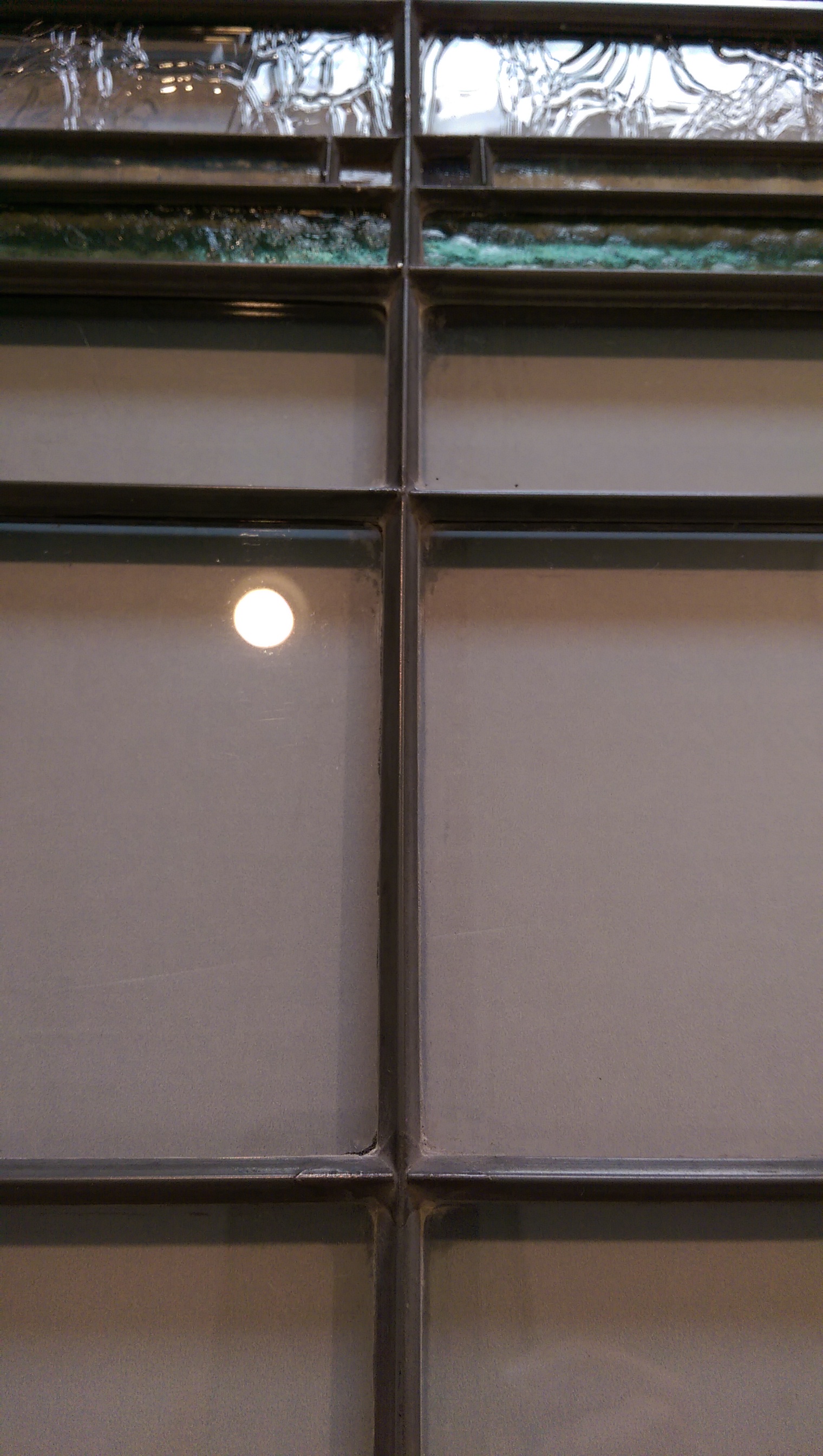

The windows are very high quality. But as the conservators removed the old grout, the crucial connector between the zinc cames and the glass, they noticed elements that suggest the studio was rushing to meet the deadline. Sharretts’s staff probably cut all the small glass pieces at once, for an assembly-line approach to manufacturing (heck, the order was for 80 windows, doors, and bookcase doors—you’d want a system in place too). Most of the upstairs windows are 46 by 25 inches, though several have slightly wider dimensions, because they were the few that were fixed or non-opening windows, not casements like the majority (the photo at top shows many second-floor casement windows open).

These two windows are undergoing conservation. The slightly wider window on the left is a fixed window, while the narrower one at right is a casement window.

Gillian Thompson, a stained-glass specialist contracted by MACC for the project, found that in places some original glass pieces were a bit too small for the window cames, especially on the slightly larger windows. Instead of cutting new ones, which would have been time-consuming and expensive for specialty glass, the artisans just added more grout to keep the glass pieces in place. She also noticed differences between the most beautiful solder joints, done by those with plenty of experience with this exacting alternative to lead, and those done by assistants—not quite so perfect—even within the same window. You could draw an analogy to a Renaissance painting workshop, where the master would complete one part and assistants would finish the rest.

This detail of zinc caming on a conserved window shows the clean solder joints of experienced glass artists.

Thompson was quick to add that “even in haste, they did a good job,” remarking that the windows, with their hand-blown craquelure glass and iridescent glass, would have been expensive luxury items for any homeowner. She also noted that the “crisp, clean, elegant” lines of zinc are perfect for the house’s angular style. Sharretts’s staff had the facility to use three to four different thicknesses of came in the glass, which Thompson likened to a line drawing in three dimensions.

In this conserved window panel, you can see that various thicknesses of zinc caming were used for emphasis.

You have to understand the level of trust that Prairie School architects had with their crucial craftsmen, those who helped realize their vision. Purcell and Elmslie trusted E. L. Sharretts’s firm with the glass for most of their projects, giving them freedom within the designs to insert punctuations of color, as seen along the border of the Purcell-Cutts House windows, where tiny boxes vary in color and number throughout the house. This sense of playfulness was perfect for the house Purcell and Elmslie called “The Little Joker,” surely a delight to move into for the Christmas of 1913.

The Purcell-Cutts House Window Conservation project has been financed in part with funds provided by the state of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society.